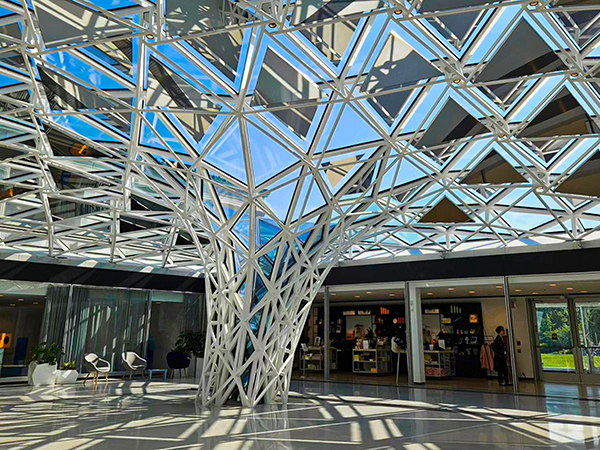

Under a canopy of glass, metal and mirrors that looks like a reflective take on the Cirque du Soleil’s Grand Chapiteau, lies an airy town square leading you to light-filled rooms filled with fine art.

Begin with stop-and-stare worthy pieces by James Tissot, John Singer Sargent, Matisse, Picasso and their contemporaries.

Or head to where works start to take a modernist turn into the worlds of Pollock, Rothko and Jasper Johns.

By Mary Luz Mejia

Buffalo AKG Art Museum

Sheets of glass span several stories and form an over 90-metre enclosed bridge leading to other parts of this complex dedicated to art.

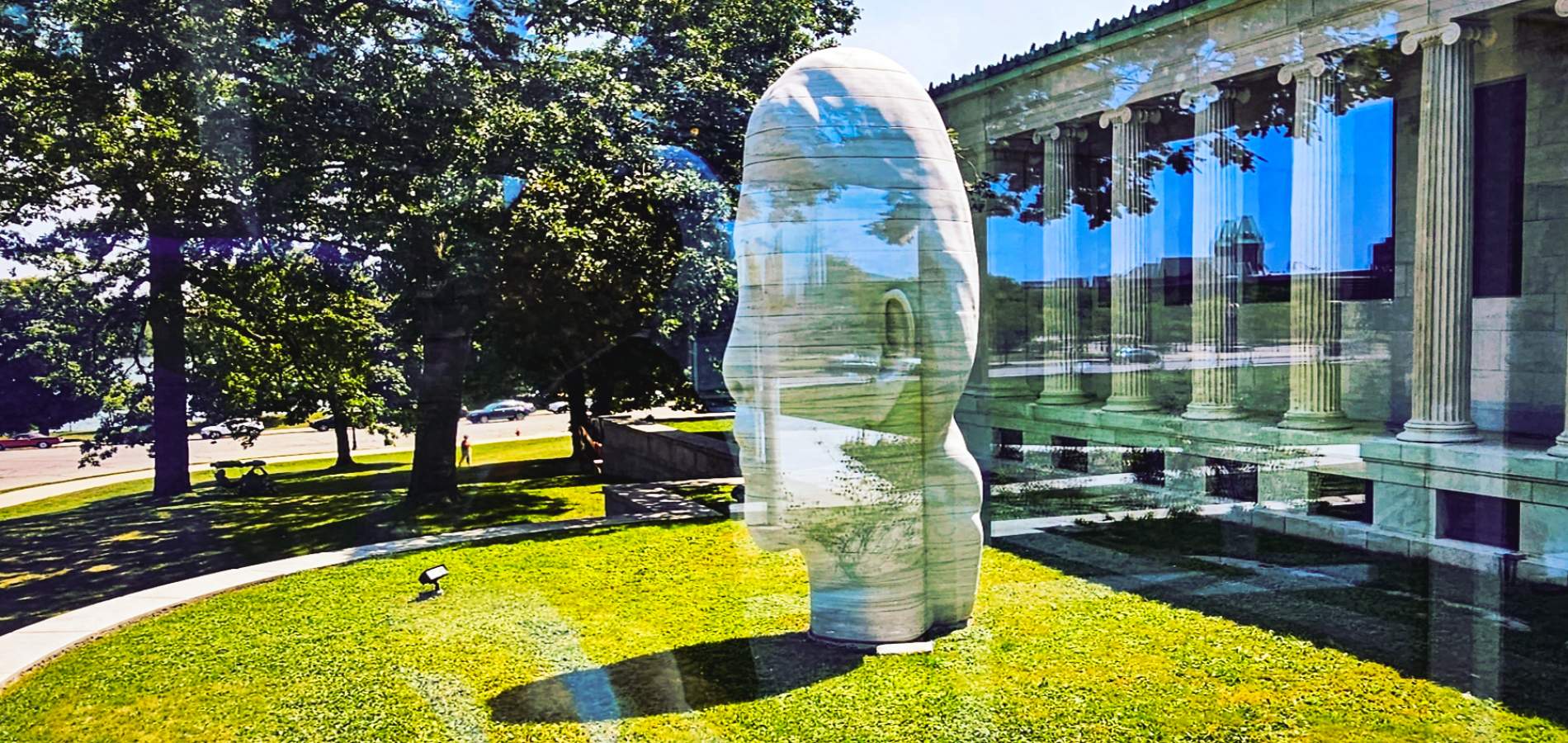

Along the way, you’ll pass Laura, an imposing sculpture by Catalan artist Jaume Plensa, standing sentinel just outside the bridge. You might think I’m describing a museum in New York City or Milan, but this is Buffalo, New York’s newly reimagined Buffalo AKG Art Museum, and it alone makes it worth visiting the Nickel City.

Glass Steel Stone: Expansion of Buffalo's AKG Art Museum.

The impressive nearly 11,000-square metre addition to the 161-year-old institution is thanks in large part to the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), lead by Shohei Shigematsu, partner at OMA North America. Andrew Mayer, Manager of Marketing and Media Relations at AKG, says that rather than merely seeking new designs for a new building, the museum sought architectural partners to work with the community, hearing their thoughts and incorporating their needs into a final design. The $64 million USD project has the desired result. It has transformed the Buffalo AKG Art Museum itself into a “canvas” (as Architectural Digest notes): not just a home for art but a space that is inclusive, warm and community-driven.

Mirror, Metal, Glass and Light

We start our tour of the Buffalo AKG Museum in Common Sky, the aforementioned ‘town square’, so-called because it covers and connects the 1905 built Robert and Elisabeth Wilmers Building and the 1962 built Seymour H. Knox Building. It was created by Studio Other Spaces – a collaboration between Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson and German architect Sebastian Behmann. The result is kaleidoscopic people-watching at its best, with folks sipping on coffees and eating brunch at the square’s Cornelia café.

Common Sky, an installation by Olafur Eliasson and Sebastian Behmann of Studio Other Spaces.

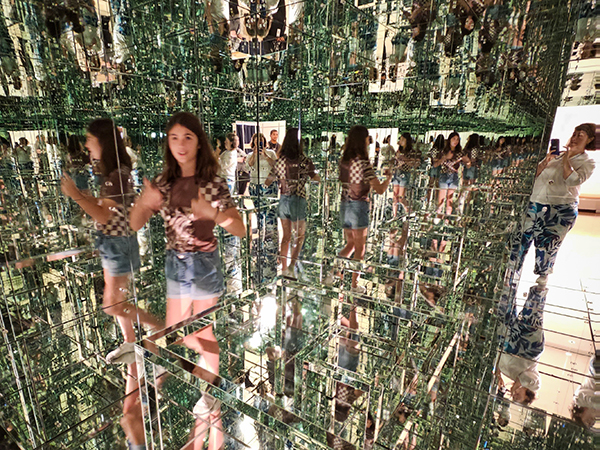

We meet museum docent Brian Gugino here and head to Lucas Samaras’s Mirrored Room (1966) in the Seymour H. Knox Building. Made entirely of mirrors, both inside and out, we take off our shoes, keep our socks on and enter the room featuring a mirrored table and chair. The result is a mesmerizing experience that offers new points of view with every movement.

Mirrored Room | Designed by Lucas Samoras, American, born Greece, 1936-2024

A Study in Colour

We see exemplary works by Cézanne, Picasso, Dalí, Miró and more – there’s so much to explore. As Gugino’s former colleague says, “There are a lot of museums out there with Pollocks and Rothkos in their collections. But the works we have are the cream." And on any given day, only 2% of the museum’s collection is on display.

On the ground floor of the Jeffrey E. Gundlach Building, Gugino introduces us to the enigmatic, abstract works of artist Clyfford Still. The museum acquired its first Still painting in 1957, with more to follow thanks to the relationship then Director Gordon Smith and Chairman of the Board Seymour H. Knox Jr. developed with the artist.

Clyfford Still's PH-1123 (1954), 1954 in the Jeffrey E. Gundlach Building.

Gugino explained that Still’s early works and innovations in abstraction fostered the Abstract Expressionist movement. His works are grand in scale and scope. The current exhibition includes all 33 of the museum’s paintings, along with documentation and photographs of the artist’s relationship with Buffalo. The painting November 1954 looks like the map of a lost continent, awash in snow with a black islet on the bottom and an orange landmass still further below. Gugino says we’re supposed to be hit with colour and form all at once – and that’s exactly the case. There’s something very powerful about his choice of colour, its placement and the brushstrokes on huge, thirteen-foot (or larger) canvases that captivate the eye.

Reflecting Other Voices

Recent acquisitions focus on the voices of other artists who see the world from their unique point of view. Take for example the stunning 2011 photographic work titled Esta finca no será demolida (This property will not be demolished) by Mexican-born Teresa Margolles. Forty photographs depict life in the border town of Ciudad Juarez – faced with years of drug-related violence – and the resilience of the people who own businesses and continue to live their lives there despite the hardships.

On our way out, there’s a live jazz concert going on at the Sculpture Terrace that’s free and open to the public. It’s these kinds of grass roots initiative at the museum and beyond, that keep Buffalo interesting and vibrant.

To Do Nearby

With so much going on in Buffalo, you’d be wise to visit the City of Good Neighbours before it changes faster than you can keep up. Visit the restored and ecologically sensitive industrial site Silo City, where former grain elevators have been turned into new-found homes for art installations including Gareth Lichty’s Warp (2016).

WARP 2016 installation by Gareth Lichty at Silo City.

At Silo City, you can enjoy the “industrial ruins,” stay for the music at Duende, or in the summer, enjoy a live theatrical performance in one of the gardens.

Stay and Dine

Less than two kilometres from the museum, on Lafayette Ave, sits InnBuffalo, the 1898 Victorian mansion of former business tycoon Herbert Hewitt turned boutique hotel. Enjoy a step back in time with lovingly resorted grand spaces featuring a Chickering piano, a speakeasy style basement (cocktails included) and fully-tiled bathrooms from the late 1800s. Innkeeper Joe is a gem and happy to make your stay special.

Inn Buffalo | 1898 Victorian mansion of former business tycoon Herbert Hewiit.

Head to Cucina at the newly restored Richardson Hotel Buffalo, for a taste of Northern Italy featuring house-made fresh pastas, risottos, grilled fish and fresh seafood. The dishes are created using locally sourced ingredients in a historic venue sitting on forty acres of park designed by Frederick Law Olmstead, the same man who designed Manhattan’s Central Park.

Sculpture at the entrance of the newly restored Richardson Hotel Buffalo.

Your private jet dream is within reach.

Photos courtesy of Mary Luz Mejia.